django學習筆記

Table of Contents

- 1. Coding Style

- 2. Layout Django Project

- 3. Setting Files

- 4. Model

- 5. Queries and the Database Layer

- 6. Function- and Class-Based Views

- 7. Function-Based Views

- 8. Class-Based Views

- 9. Form Fundamentals

- 10. Common Patterns for Forms

- 11. Templates

- 12. Template Tags and Filters

- 13. Building REST APIs

- 14. Working With the Django Admin

- 15. Dealing With the User Model

- 16. Third-Party Packages

- 17. Testing

- 17.1. Useful Library for Testing Django Projects

- 17.2. How to Structure Tests

- 17.3. How to Write Unit Tests

- 17.3.1. Each Test Method Tests One Thing

- 17.3.2. For Views, When Possible Use the Request Factory

- 17.3.3. Don't Repeat Yourself Doesn't Apply to Writing Tests

- 17.3.4. Don't Rely on Fixtures

- 17.3.5. Things That Should Be Tested

- 17.3.6. Test for Failure

- 17.3.7. Use Mock to Keep Unit Tests From Touching the World

- 17.3.8. Use Fancier Assertion Methods

- 17.3.9. Document the Purpose of Each Test

- 17.4. What About Integration Tests?

- 17.5. Continuous Integration

- 17.6. Setting Up the Test Coverage Game

- 18. Documentation

- 19. Finding and Reducing Bottlenecks

- 19.1. Should You Even Care?

- 19.2. Speed Up Query-Heavy Pages

- 19.3. Know What Doesn't Belong in the Database

- 19.4. Cache Queries With Memcached or Redis

- 19.5. Identify Specific Places to Cache

- 19.6. Compression and Minification of HTML, CSS, and JavaScript

- 19.7. Use Upstream Caching or a Content Delivery Network

- 20. Asynchronous Task Queues

- 21. Security

- 22. Logging

- 23. Signals: Use Cases and Avoidance Techniques

- 24. Utilities

- 25. Deployment:Platforms as a Service

- 26. Deploying Django Projects

- 27. Continuous Integration

- 28. Debugging

- 29. Internationalization and Localization

- 30. Security Settings Reference

- 31. Some Useful Packages

- 32. Reference

django學習筆記

隨筆亂記,陸續增加中

1 Coding Style

1.1 Use Explicit Relative Imports

here’s a table of the different Python import types and when to use them in Django projects:

| Code | Import Type | Usage |

|---|---|---|

| from core.views import FoodMixin | absolute import | Use when importing from outside the current app |

| from .models import WaffleCone | explicit relative | Use when importing from another module in the current app |

| from models import WaffleCone | implicit relative | Often used when importing from another module in the current app, but not a good idea |

2 Layout Django Project

For Example:

icecreamratings project/: git repository root

icecreamratings/: project root

products/, ratings/…etc: app root

icecreamratings_project/ |

可參考github上大大寫好的django project layout工具吧

https://github.com/pydanny/cookiecutter-django

3 Setting Files

3.1 如何處理多環境設定(production, staging, local)

將setting files分開成各個環境,所有setting file全部進入git控管

底下為例子,在<repository root>/config/settings

settings/ |

local設定繼承自base

# settings/local.py |

個人設定,繼承自local

# settings/dev_pydanny.py |

執行時用以下方式指定setting file執行

django-admin shell --settings=twoscoops.settings.local |

在server上可以設定環境變數DJANGO SETTINGS MODULE and PYTHONPATH來指定setting file,或利用virtualenv來設定(add Export to the end of virtualenv's bin/activate)

3.2 重要的secret key問題(secret key不該進入version control)

secret key不該進入version control所以不要把它放在setting file中

最好是放在environment variable,setting file中用os.environ["SOME_SECRET_KEY"]去拿

linux下將以下放到.bashrc, .bash_profile, or .profile

或利用virtualenv來設定(add Export to the end of virtualenv's bin/activate)

export SOME_SECRET_KEY=1c3-cr3am-15-yummy |

setting file用以下方式拿secret key

# Top of settings/production.py |

上述方式在拿不到environ variable時錯誤訊息會是key_error,不甚好,可在base.py中加入以下改良

# settings/base.py |

SOME_SECRET_KEY = get_env_variable("SOME_SECRET_KEY") |

3.3 當環境限制無法使用environment variable時怎麼做呢

將secret_key放進json file(or xml, yml …etc),setting file中利用json util將secret_key讀出,注意此secret file不該進入version control

{ |

# settings/base.py |

3.4 Requirements Files也要照環境分開

不同環境可能需要裝不同package(ex: local才需要debug工具)

在<repository root>/requirements

requirements/ |

in base.txt

Django==1.8.0 |

in local.txt

-r base.txt # includes the base.txt requirements file |

in production.txt

-r base.txt # includes the base.txt requirements file |

裝package時用以下指令指定requirements檔案安裝

$ pip install -r requirements/local.txt |

3.5 Setting Files中的Path不要使用Absolute Path

利用Unipath (http://pypi.python.org/pypi/Unipath/)

# At the top of settings/base.py |

或用python內建的os.path

# At the top of settings/base.py |

4 Model

4.1 Model Inheritance

當重複field太多時,可考慮abstract base inheritance,例如幾乎每個model都要有created, modified

- Abstract base classes: 實際上DB不會有parent table

- multi-table inheritance: DB確實會長出parent table and child table然後用foreign key連結

- proxy models

不要使用multi-table inheritance,由於其實是使用foreign key處理所以會有效能問題

以下為例子

core.models.TimeStampedModel裡有常用的created and modified field

flavors.Flovor繼承TimeStampedModel的field

注意

class Meta:

abstract = True

# core/models.py |

# flavors/models.py |

4.2 Model Design Ordering

- Start Normalized

- Cache Before Denormalizing

- Denormalize Only if Absolutely Needed(try cache, row SQL, indexes)

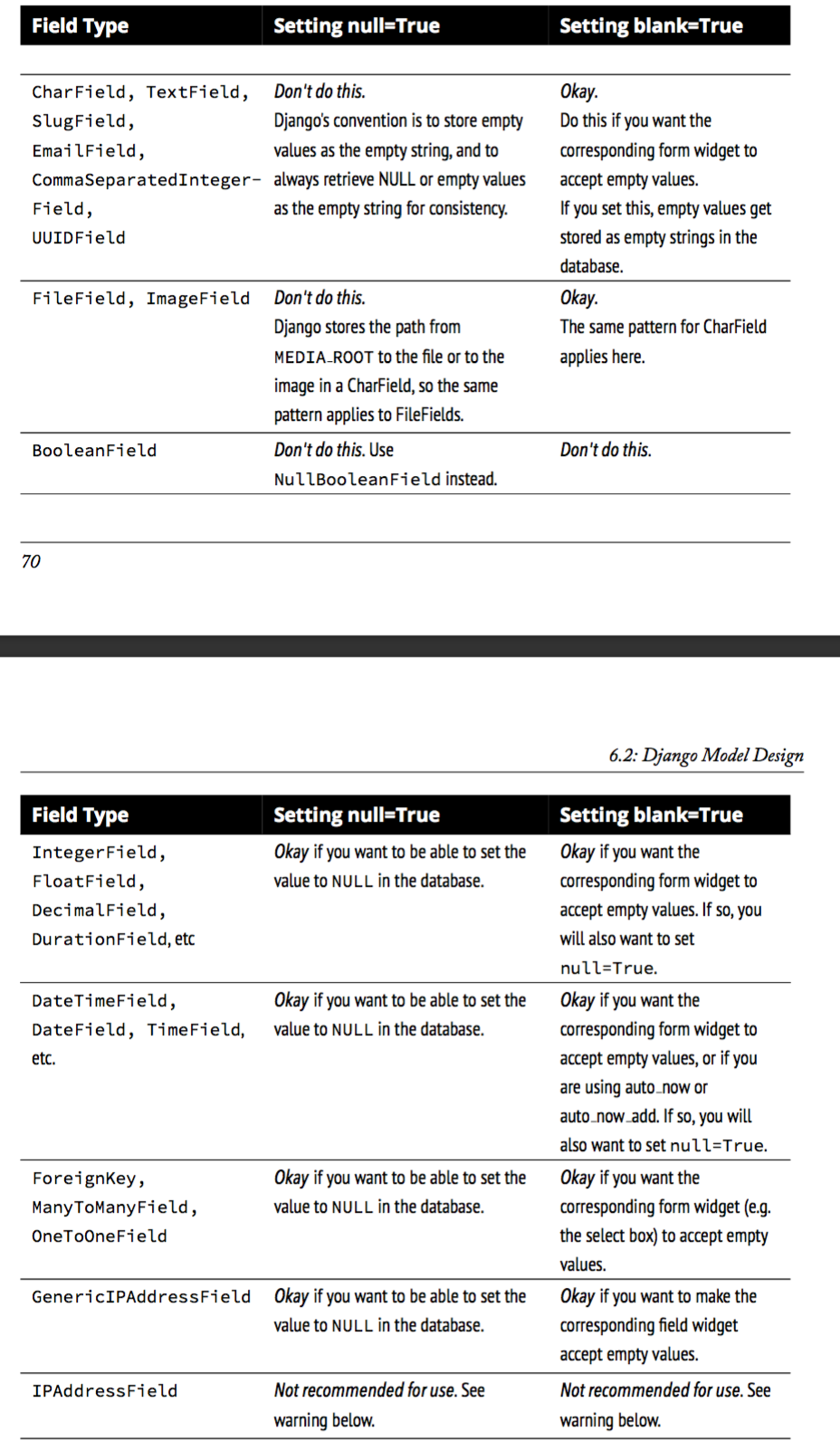

4.3 When to Use Null and Blank

4.4 When to Use BinaryField

Don't Serve Files From BinaryField. Use FileField!!!

- MessagePack-formatted content.

- Raw sensor data.

- Compressed data e.g. the type of data Sentry stores as a BLOB, but is required to base64-encode due to legacy issues.

4.5 Try to Avoid Using Generic Relations

Cons:

- Reduction in speed of queries due to lack of indexing between models.

- Danger of data corruption as a table can refer to another against a non-existent record.

So:

- Try to avoid generic relations and GenericForeignKey.

- If you think you need generic relations, see if the problem can be solved through better model design or the new PostgreSQL elds.

- If usage can’t be avoided, try to use an existing third-party app. e isolation a third-party app provides will help keep data cleaner.

4.6 The Model meta API

Main Usages:

- Get a list of a model’s fields.

- Get the class of a particular eld for a model (or its inheritance chain or other info derived from such).

- Ensure that how you get this information remains constant across future Django versions.

Examples:

- Building a Django model introspection tool.

- Building your own custom specialized Django form library.

- Creating admin-like tools to edit or interact with Django model data.

- Writing visualization or analysis libraries, e.g. analyzing info only about elds that start with “foo”.

4.7 Fat Models

將跟DB有關的邏輯從view中抽出放到Model中包裝是好的設計,但project到最後會發生Model肥大的問題,一個Model數千行這就不好了,底下提供兩個解法

- Model Behaviors Pattern: http://blog.kevinastone.com/django-model-behaviors.html

- Mixin

5 Queries and the Database Layer

5.1 Use get object or 404() for Single Objects instead of get()

- Only use it in views.

- Don’t use it in helper functions, forms, model methods or anything that is not a view or directly view related.

5.2 Be Careful With Queries That Might Throw Exceptions

5.2.1 ObjectDoesNotExist vs. DoesNotExist

ObjectDoesNotExist can be applied to any model object, whereas DoesNotExist is for a speci c model.

from django.core.exceptions import ObjectDoesNotExist |

5.2.2 When You Just Want One Object but Get Three Back

check for a MultipleObjectsRe- turned exception

from flavors.models import Flavor |

5.3 Transactions

5.3.1 Wrapping Each HTTP Request in a Transaction

# settings/base.py |

non atomic function include atomic code:

# flavors/views.py |

5.3.2 Explicit Transaction Declaration

6 Function- and Class-Based Views

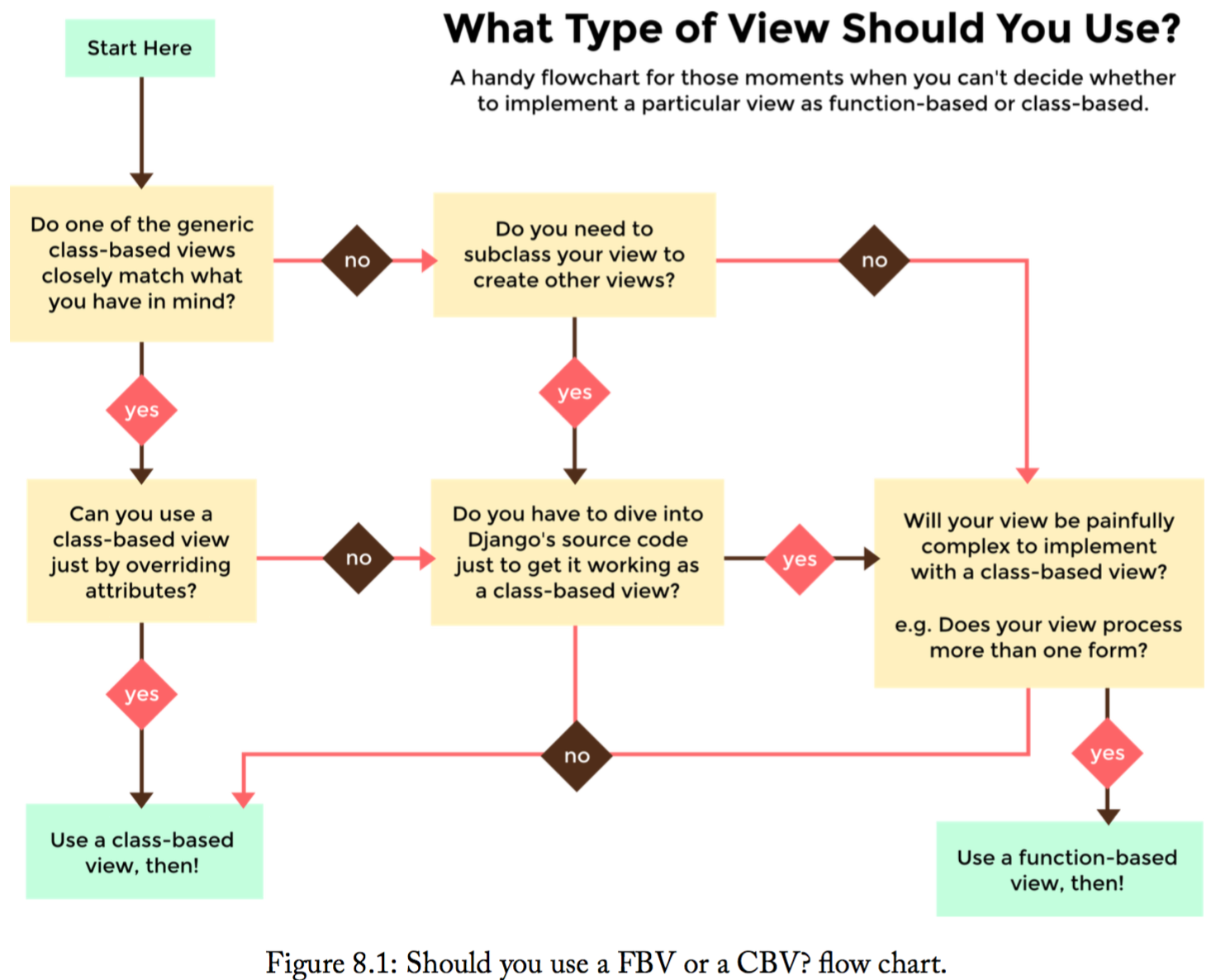

6.1 When to Use FBVs or CBVs

6.2 Keep View Logic Out of URLConfs

Bad Example:

from django.conf.urls import url |

Good view example:

# tastings/views.py |

Good urls example:

# tastings/urls.py |

6.3 Use URL Namespaces

In the root URLConf we would add:

# urls.py at root of project |

view example:

# tastings/views.py snippet |

template example:

{% extends "base.html" %} |

6.4 Django Views Are Functions

Class-Based Views Are Actually Called as Functions

# simplest_views.py |

6.5 Don't Use locals() as Views Context

Bad example:

def ice_cream_store_display(request, store_id): |

Good example:

def ice_cream_store_display(request, store_id): |

7 Function-Based Views

7.1 Use Decorator To Modify Request And Response

Here’s a sample decorator template for use in function-based views:

functools.wraps() is a convenience tool that copies over metadata including critical data like docstrings to the newly decorated function.

# simple decorator template import functools |

check_sprinkles is a decorator to modify request:

# sprinkles/decorators.py |

Then we attach it to the function thus:

# views.py |

8 Class-Based Views

8.1 Guidelines When Working With CBVs

- Less view code is better.

- Never repeat code in views.

- Views should handle presentation logic. Try to keep business logic in models when possible, or in forms if you must.

- Keep your views simple.

- Don’t use CBVs to write custom 403, 404, and 500 error handlers. Use FBVs instead.

- Keep your mixins simpler.

8.2 Using Mixins With CBVs

The rules follow Python’s method resolution order, which in the most simplistic de nition possible, proceeds from left to right:

- The base view classes provided by Django always go to the right.

- Mixins go to the left of the base view.

- Mixins should inherit from Python’s built-in object type.

Example of the rules in action:

from django.views.generic import TemplateView |

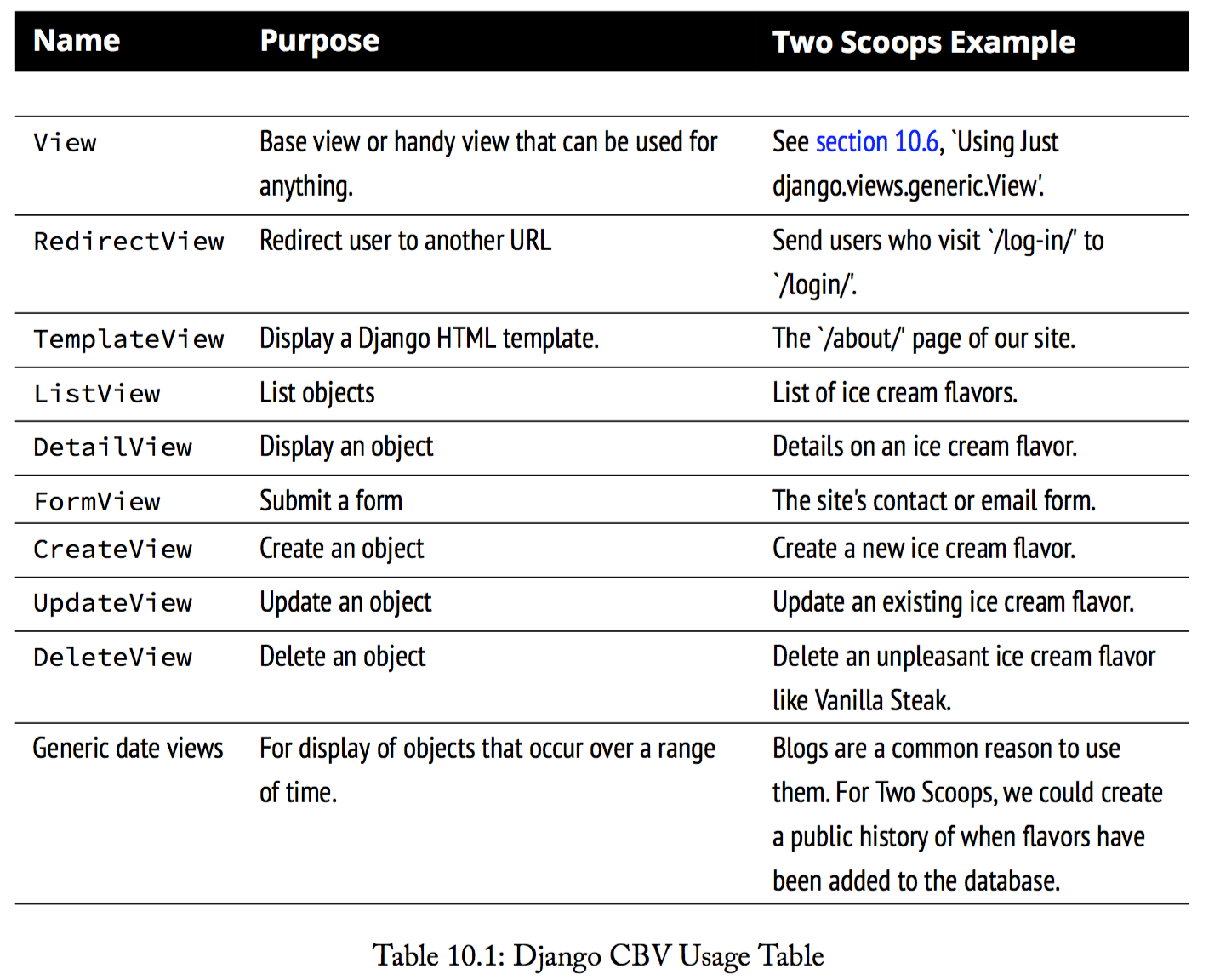

8.3 Which Django GCBV Should Be Used for What Task?

8.4 General Tips for Django CBVs

8.4.1 Constraining Django CBV/GCBV Access to Authenticated Users

Use django-braces LoginRequiredMixin

# flavors/views.py |

8.4.2 Performing Custom Actions on Views With Valid Forms

from django.views.generic import CreateView |

To perform custom logic on form data that has already been validated, simply add the logic to formvalid(). e return value of formvalid() should be a django.http.HttpResponseRedirect.

8.4.3 Performing Custom Actions on Views With Invalid Forms

from django.views.generic import CreateView |

8.4.4 Using the View Object

If you are using class-based views for rendering content, consider using the view object itself to provide access to properties and methods that can be called by other method and properties. ey can also be called from templates. For example:

from django.utils.functional import cached_property |

The nice thing about this is the various avors/ app templates can now access this property:

{# flavors/base.html #} |

8.5 How GCBVs and Forms Fit Together

First, let’s define a flavor model to use in this section’s view examples:

# flavors/models.py |

8.5.1 Views + ModelForm Example

Here we have the following views:

- FlavorCreateView corresponds to a form for adding new flavors.

- FlavorUpdateView corresponds to a form for editing existing flavors.

- FlavorDetailView corresponds to the con rmation page for both avor creation and flavor updates.

Views:

# flavors/views.py |

Template:

{# templates/flavors/flavor_detail.html #} |

8.5.2 Views + Form Example

Implemente flavor search page

We add the following code to flavors/views.py:

from django.views.generic import ListView |

Template:

{# templates/flavors/_flavor_search.html #} |

8.6 Using Just django.views.generic.View

What we find really useful, even on projects which use a lot of generic class-based views, is using the django.views.generic.View class with a GET method for displaying JSON, PDF or other non-HTML content. All the tricks that we’ve used for rendering CSV, Excel, and PDF les in function-based views apply when using the GET method. For example:

from django.http import HttpResponse . |

9 Form Fundamentals

9.1 Validate All Incoming Data With Django Forms

舉個input data為csv file的例子

Bad Example:

import csv import StringIO |

以上Bad example在Purchase create前需要自己寫input data驗證code

Good Example:

import csv import StringIO |

利用django ModelForm的is_valid來做input驗證

9.2 Always Use CSRF Protection and POST With HTTP Forms That Modify Data

You should use Django’s CsrfViewMiddleware as blanket protection across your site rather than manually decorating views with csrf protect.

You should use Django’s CSRF protection even when posting data via AJAX.

9.3 Understand How to Add Django Form Instance Attributes

Inserting the request.user object into forms

form:

from django import forms |

view:

from django.views.generic import UpdateView |

9.4 Know How Form Validation Works

Form validation workflow:

- If the form has bound data, form.is valid() calls the form.full clean() method.

- form.fullclean() iterates through the form fields and each field validates itself:

- Data coming into the eld is coerced into Python via the to python() method or raises a ValidationError.

- Data is validated against eld-speci c rules, including custom validators. Failure raises a ValidationError.

- If there are any custom clean <field>() methods in the form, they are called at this time.

- Data coming into the eld is coerced into Python via the to python() method or raises a ValidationError.

- form.fullclean() executes the form.clean() method.

- If it’s a ModelForm instance, form. post clean() does the following:

- Sets ModelForm data to the Model instance, regardless of whether form.is valid() is True or False.

- Calls the model’s clean() method. For reference, saving a model instance through the ORM does not call the model’s clean() method.

- Sets ModelForm data to the Model instance, regardless of whether form.is valid() is True or False.

9.4.1 ModelForm Data Is Saved to the Form, Then the Model In- stance

In a ModelForm, form data is saved in two distinct steps:

- First, form data is saved to the form instance.

- Later, form data is saved to the model instance.

For example, perhaps you need to catch the details of failed submission attempts for a form, saving both the user-supplied form data as well as the intended model instance changes.

# core/models.py |

# flavors/views.py import json |

9.5 Add Errors to Forms with Form.add error()

We can streamline Form.clean() with the Form.add error() method.

from django import forms |

10 Common Patterns for Forms

10.1 Pattern 1: Simple ModelForm With Default Validators

# flavors/views.py |

- FlavorCreateView and FlavorUpdateView are assigned Flavor as their model.

- Both views auto-generate a ModelForm based on the Flavor model.

- Those ModelForms rely on the default field validation rules of the Flavor model.

10.2 Pattern 2: Custom Form Field Validators in ModelForms

write validator:

# core/validators.py |

In Django, a custom field validator is simply a function that raises an error if the submitted argument doesn’t pass its test.

validator可以加在兩個地方

10.2.1 put validator in Model

# core/models.py |

# flavors/models.py |

10.2.2 put validator in Form

# flavors/forms.py |

# flavors/views.py |

10.3 Pattern 3: Overriding the Clean Stage of Validation

use cases:

- Multi-field validation

- Validation involving existing data from the database that has already been validate

Django provides a second stage and process for validating incoming data, this time via the clean() method and clean <field name>() methods.

- clean() validate two or more fields against each other.

- clean <field name>() validate against persistent data.

Example:

clean slug(): prevent users from ordering flavors that are out of stock

clean(): validate the flavor and toppings fields against each other

# flavors/forms.py |

10.4 Pattern 4: Hacking Form Fields (2 CBVs, 2 Forms, 1 Model)

example:

IceCreamStore在create時只需要填入title, address,update時再強制其補上phone, description

IceCreamStore Model:

from django.core.urlresolvers import reverse |

First we see the bad approach:

# stores/forms.py |

上面的方法幾乎是copy了model中的field,想像一下若我們需要在description中加入help text,就必須同時在model與form中同時加上不然沒有作用,這不是一個好的設計

Now we use form.fields[].required to do this.

Form:

# stores/forms.py |

Views:

# stores/views |

10.5 Pattern 5: Reusable Search Mixin View

In this example, we’re going to cover how to reuse a search form in two views that correspond to two different models.

simple search mixin for our view:

# core/views.py |

views:

# add to flavors/views.py |

# add to store/views.py |

template:

{# form to go into stores/store_list.html template #} |

{# form to go into flavors/flavor_list.html template #} |

11 Templates

11.1 Keep Templates Mostly in templates/

Template layout:

templates/ |

However, some tutorials advocate putting templates within a subdirectory of each app. We find that the extra nesting is a pain to deal with

freezers/ |

11.2 Template Architecture Patterns

11.2.1 2-Tier Template Architecture Example

all templates inherit from a single root base.html

templates/ |

This is best for sites with a consistent overall layout from app to app.

11.2.2 3-Tier Template Architecture Example

- Each app has a base_<app name>.html template. App-level base templates share a common parent base.html template.

- Templates within apps share a common parent base_<app name>.html template.

- Any template at the same level as base.html inherits base.html.

templates/ |

The 3-tier architecture is best for websites where each section requires a distinctive layout. For example, a news site might have a local news section, a classified ads section, and an events section. Each of these sections requires its own custom layout.

11.2.3 Flat Is Better Than Nested

template層數越少越好維護

11.3 Limit Processing in Templates

Whenever you iterate over a queryset in a template, ask yourself the following questions:

- How large is the queryset? Looping over gigantic querysets in your templates is almost always a bad idea.

- How large are the objects being retrieved? Are all the fields needed in this template?

- During each iteration of the loop, how much processing occurs?

Let’s now explore some examples of template code that can be rewritten more efficiently.

Model:

# vouchers/models.py |

11.3.1 Gotcha 1: Aggregation in Templates

- Don’t iterate over the entire voucher list in your template’s JavaScript section, using JavaScript variables to hold age range counts.

- Don’t use the add template lter to sum up the voucher counts.

11.3.2 Gotcha 2: Filtering With Conditionals in Templates

A very bad way to implement this would be with giant loops and if statements at the template level.

Bad Example:

<h2>Greenfelds Who Want Ice Cream</h2> |

Good Example

views:

# vouchers/views.py |

template:

<h2>Greenfelds Who Want Ice Cream</h2> |

11.3.3 Gotcha 3: Complex Implied Queries in Templates

Bad Example:

{# list generated via User.object.all() #} |

One quick correction is to use the Django ORM’s select related() method:

{% comment %} |

11.3.4 Gotcha 4: Hidden CPU Load in Templates

需要大量CPU LOAD的code不該在template中,例如save image to file system

11.3.5 Gotcha 5: Hidden REST API Calls in Templates

REST API call不該放在template中,由於REST API可能會跑很久

建議在javascript code or view 中處理REST API call

- JavaScript code so after your project serves out its content, the client’s browser handles the work. is way you can entertain or distract the client while they wait for data to load.

- The view’s Python code where slow processes might be handled in a variety of ways including message queues, additional threads, multiprocesses, or more.

11.4 Exploring Template Inheritance

base.html:

{# simple base.html #} |

The base.html file contains the following features:

- A title block containing “Two Scoops of Django”.

- A stylesheets block containing a link to a project.css file used across our site.

- A content block containing “<h1>Two Scoops</h1>”.

| Template Tag | Purpose |

|---|---|

| {% load %} | Loads the staticfiles built-in template tag library |

| {% block %} | Since base.html is a parent template, these define which child blocks can be filled in by child templates. We place links and scripts inside them so we can override if necessary. |

| {% static %} | Resolves the named static media argument to the static media server. |

we’ll have a simple about.html inherit the following from it:

- A custom title.

- The original stylesheet and an additional stylesheet.

- The original header, a sub header, and paragraph content.

- The use of child blocks.

- The use of the template variable.

{% extends "base.html" %} |

it generates the following HTML:

<html> |

| Template Object | Purpose |

|---|---|

| {% extends %} | Informs Django that about.html is inheriting or extending from base.html |

| {% block %} | Since about.html is a child template, block overrides the content provided by base.html. This means our title will render as <title>Audrey and Daniel</title> |

| {{ block.super }} | When placed in a child template's block, it ensures that the parent's content is also included in the block. In the content block of the about.html template, this will render <h1>Two Scoops</h1>. |

11.5 block.super Gives the Power of Control

Here are three examples:

Template using both project.css and a custom link:

{% extends "base.html" %} |

Dashboard template that excludes the project.css link:

{% extends "base.html" %} |

Template just linking the project.css file:

{% extends "base.html" %} |

11.6 Useful Things to Consider

11.6.1 Avoid Coupling Styles Too Tightly to Python Code

Aim to control the styling of all rendered templates entirely via CSS and JS.

- If you have magic constants in your Python code that are entirely related to visual design layout, you should probably move them to a CSS file.

- The same applies to JavaScript.

11.6.2 Common Conventions

- We prefer underscores over dashes in template names, block names, and other names in tem- plates. Most Django users seem to follow this convention. Why? Well, because underscores are allowed in names of Python objects but dashes are forbidden.

- We rely on clear, intuitive names for blocks. {% block javascript %} is good.

- We include the name of the block tag in the endblock. Never write just {% endblock %}, include the whole {% endblock javascript %}.

- Templates called by other templates are prefixed with ‘_’. is applies to templates called via {% include %} or custom template tags. It does not apply to templates inheritance controls such as {% extends %} or {% block %}.

11.6.3 Location

Templates should usually go into the root of the Django project, at the same level as the apps.

The only exception is when you bundle up an app into a third-party package. That packages template directory should go into app directly.

11.6.4 Use Named Context Objects

use {{ topping list }} and {{ topping }} in your templates, instead of {{ object list }} and {{ object }}

11.6.5 Use URL Names Instead of Hardcoded Paths

A common developer mistake is to hardcode URLs in templates like this:

<a href="/flavors/"> |

Instead, we use the {% url %} tag and references the names in our URLConf les:

<a href="{% url 'flavors_list' %}"> |

11.6.6 Debugging Complex Templates

A trick recommended by Lennart Regebro is that when templates are complex and it becomes dif- cult to determine where a variable is failing, you can force more verbose errors through the use of the string if invalid option in OPTIONS of your TEMPLATES setting:

# settings/local.py |

11.7 Error Page Templates

It’s standard practice to create at least 404.html and 500.html templates.

We suggest serving your error pages from a static file server (e.g. Nginx or Apache) as entirely self- contained static HTML files. That way, if your entire Django site goes down but your static le server is still up, then your error pages can still be served.

GitHub’s 404 and 500 error pages are great examples of fancy but entirely static, self-contained error pages:

- https://github.com/404

- https://github.com/500

- All CSS styles are inline in the head of the same HTML page, eliminating the need for a separate stylesheet.

- All images are entirely contained as data within the HTML page. ere are no <img> links to external URLs.

- All JavaScript needed for the page is contained within the HTML page. There are no external links to JavaScript assets.

For more information, see the Github HTML Styleguide:

12 Template Tags and Filters

12.1 Filters Are Functions

Filters are functions that accept just one or two arguments.

大多數的filters都只是作很簡單的事,通常都是將實作寫在utils.py,再由filters去import utils.py

可參考django的default filters實作:https://github.com/django/django/blob/stable/1.8.x/django/template/defaultfilters.py

django.template.defaultfilters.slugify是呼叫django.utils.text.slugify

12.1.1 When to Write Filters

Filters are good for modifying the presentation of data, and they can be readily reused in REST APIs and other output formats.

12.2 Custom Template Tags

- Template Tags Are Harder to Debug

- Template Tags Make Code Reuse Harder

- The Performance Cost of Template Tags

12.2.1 When to Write Template Tags

Think these before writing custom tags:

- Anything that causes a read/write of data might be better placed in a model or object method.

- Since we implement a consistent naming standard across our projects, we can add an abstract base class model to our core.models module. Can a method or property in our project’s abstract base class model do the same work as a custom template tag?

When should you write new template tags? We recommend writing them in situations where they are only responsible for rendering of HTML. For example, projects with very complex HTML layouts with many different models or data types might use them to create a more exible, understandable template architecture.

12.3 Naming Your Template Tag Libraries

The convention we follow is <app name>_tags.py.

- flavors_tags.py

- blog_tags.py

12.4 Loading Your Template Tag Modules

{% extends "base.html" %} |

12.4.1 Watch Out for This Crazy Anti-Pattern

Don't Use This

# Don't use this code! |

13 Building REST APIs

13.1 Fundamentals of Basic REST API Design

HTTP method:

| Purpose of Request | HTTP Method | Rough SQL equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| Create a new resource | POST | INSERT |

| Read an existing resource | GET | SELECT |

| Request the metadata of an existing resource | HEAD | |

| Update an existing resource | PUT | UPDATE |

| Update part of an existing resource | PATCH | UPDATE |

| Delete an existing resource | DELETE | DELETE |

| Return the supported HTTP methods for the given URL | OPTIONS | |

| Echo back the request | TRACE | |

| Tunneling over TCP/IP (usually not implemented) | CONNECT |

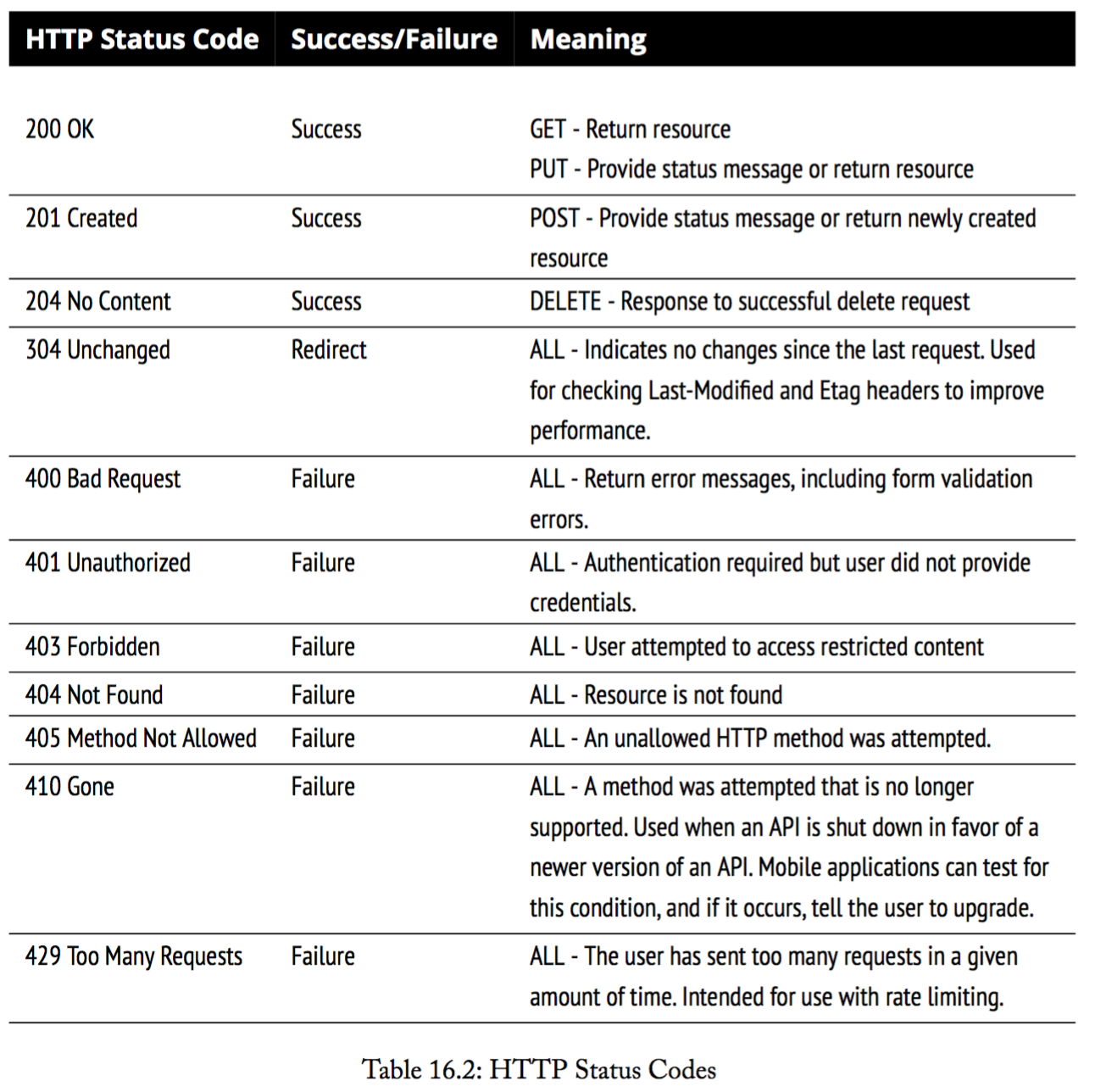

some common HTTP status codes:

13.2 Implementing a Simple JSON API

use django-rest-framework

model:

# flavors/models.py |

Define the serializer class:

from rest_framework import serializers |

Views:

# flavors/views |

flavors/urls.py:

# flavors/urls.py |

| Url | View | Url Name (same) |

|---|---|---|

| flavors/api | FlavorCreateReadView | flavor_rest api |

| flavors/api:slug/ | FlavorReadUpdateDeleteView | flavor_rest api |

Don't forget to add authenticate and permissions:

13.3 REST API Architecture

13.3.1 Code for a Project Should Be Neatly Organized

For example, we might place all our views, serializers, and other API components in an app titled apiv4.

The downside is the possibility for the API app to become too large and disconnected from the apps that power it. Hence why we consider an alternative in the next subsection.

13.3.2 Code for an App Should Remain in the App

REST APIs are just views. For simpler, smaller projects, REST API views should go into views.py or viewsets.py modules

The downside is that if there are too many small, interconnecting apps, it can be hard to keep track of the myriad of places API components are placed. Hence why we considered another approach in the previous subsection.

13.3.3 Grouping API URLs

If you have REST API views in multiple Django apps, how do you build a project-wide API that looks like this?

api/flavors/ # GET, POST |

# core/api.py |

13.3.4 Version Your API

It’s a good practice to abbreviate the urls of your API with the version number e.g. /api/v1/flavors or /api/v1/users and then as the API changes, /api/v2/flavors or /api/v2/users.

13.4 Shutting Down an External API

- Notify User

- Replace API With 410 Error View

# core/apiv1_shutdown.py |

13.5 Rate Limiting Your API

Rate limiting is when an API restricts how many requests can be made by a user of the API within a period of time.

14 Working With the Django Admin

14.1 It's Not for End Users

The Django admin interface is designed for site administrators, not end users.

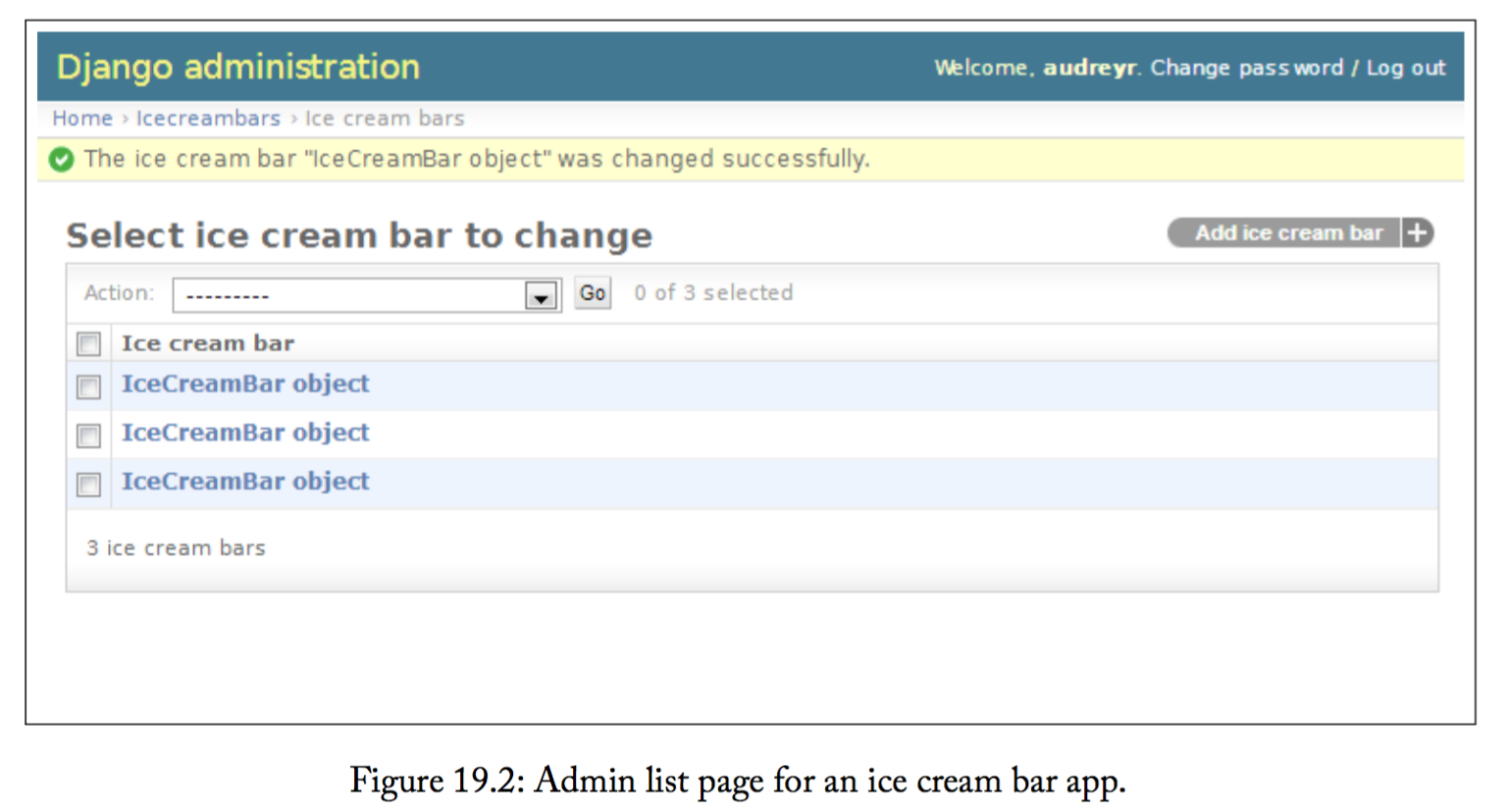

14.2 Add str to Model

The default admin page for a Django app looks something like this:

Implementing __str__():

from django.db import models |

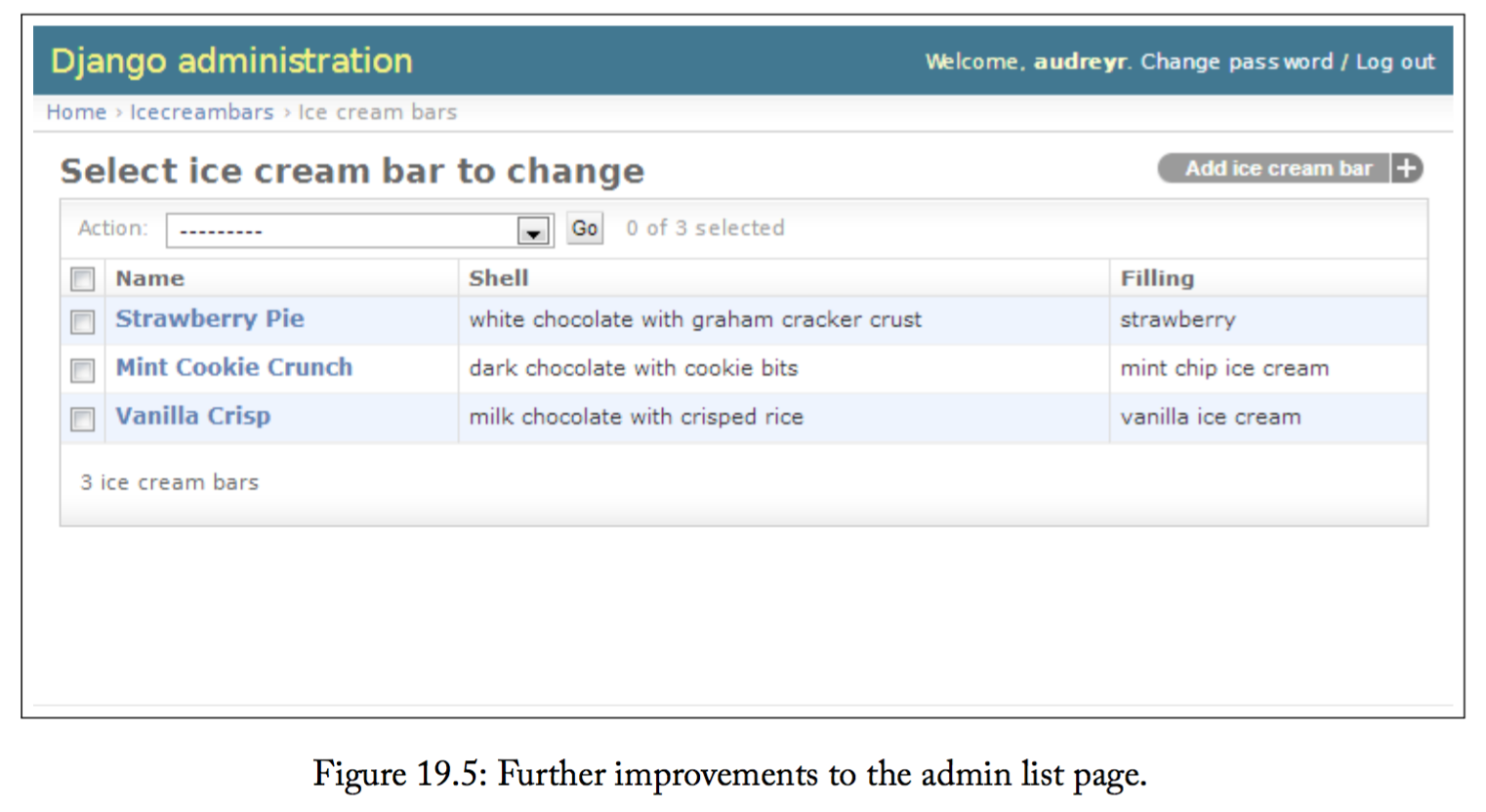

The result:

If you still want to show data for additional elds on the app’s admin list page, you can then use list display:

from django.contrib import admin |

The result with the specified fields:

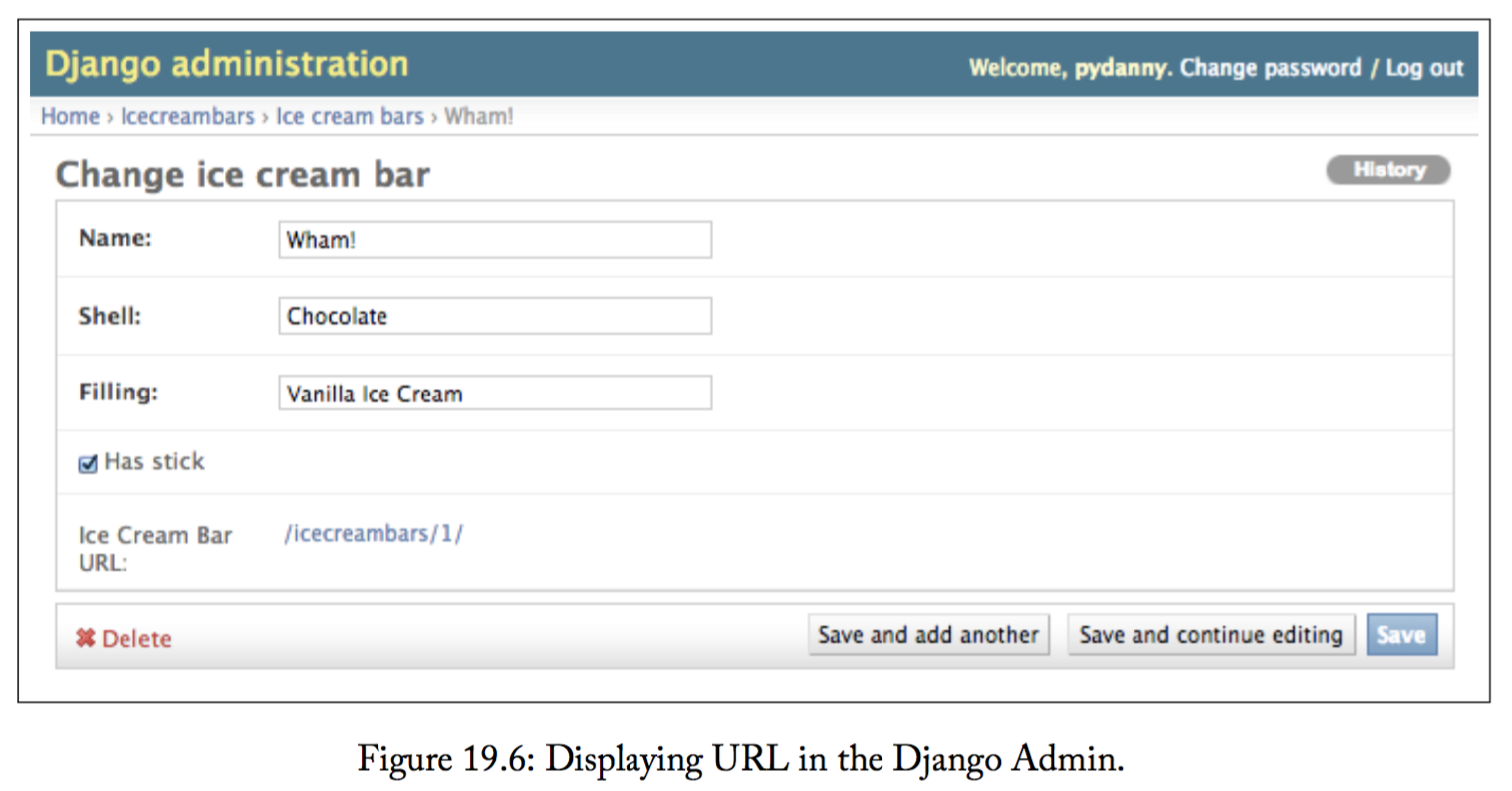

14.3 Adding Callables to ModelAdmin Classes

For example, it’s not uncommon to want to see the exact URL of a model instance in the Django admin.

from django.contrib import admin |

14.4 Django's Admin Documentation Generator

- pip install docutils into your project’s virtualenv.

- Add django.contrib.admindocs to your INSTALLED APPS.

- Add (r'ˆadmin/doc/', include('django.contrib.admindocs.urls')) to your root URLConf. Make sure it’s included before the r'ˆadmin/' entry, so that requests to admin/doc don’t get handled by the latter entry.

- Optional : Linking to templates requires the ADMIN FOR setting to be con gured.

- Optional : Using the admindocs bookmarklets requires the XViewMiddleware to be installed.

14.5 Securing the Django Admin and Django Admin Docs

15 Dealing With the User Model

15.1 Use Django's Tools for Finding the User Model

The advised way to get to the user class is as follows:

# Stock user model definition |

15.1.1 Use settings.AUTH_USER_MODEL for Foreign Keys to User

from django.conf import settings |

15.1.2 Don't Use get user model() for Foreign Keys to User

This is bad, as it tends to create import loops.

# DON'T DO THIS! |

15.2 Custom User Fields for Django 1.8 Projects

15.2.1 Option 1: Subclass AbstractUser

Choose this option if you like Django’s User model elds the way they are, but need extra fields.

# profiles/models.py |

The other thing you have to do is set this in your settings:

AUTH_USER_MODEL = "profiles.KarmaUser" . |

15.2.2 Option 2: Subclass AbstractBaseUser

AbstractBaseUser is the bare-bones option with only 3 fields: password, last login, and is active.

Choose this option if:

- You’re unhappy with the elds that the User model provides by default, such as first name and last name.

- You prefer to subclass from an extremely bare-bones clean slate but want to take advantage of the AbstractBaseUser sane default approach to storing passwords.

If you want to go down this path, we recommend the following reading:

- Official Django Documentation Example http://2scoops.co/1.8-custom-user-model-example

- Source code of django-authtools (Especially admin.py,forms.py,andmodels.py) https://github.com/fusionbox/django-authtools

15.2.3 Option 3: Linking Back From a Related Model

Use Case: Creating a Third Party Package

- We are creating a third-party package for publication on PyPI.

- The package needs to store additional information per user, perhaps a Stripe ID or another payment gateway identifier.

- We want to be as unobtrusive to the existing project code as possible. Loose coupling!

Use Case: Internal Project Needs

- We are working on our own Django project.

- We want different types of users to have different fields.

- We might have some users with a combination of different user types.

- We want to handle this at the model level, instead of at other levels.

- We want this to be used in conjunction with a custom user model from options #1 or #2.

# profiles/models.py |

16 Third-Party Packages

PyPI (https://pypi.python.org/pypi)

Django Packages (https://www.djangopackages.com/)

16.1 Wiring Up Django Packages: The Basics

- Step 1: Read the Documentation for the Package

- Step 2: Add Package and Version Number to Your Requirements

- Step 3: Install the Requirements Into Your Virtualenv

- Step 4: Follow the Package's Installation Instructions Exactl

17 Testing

17.1 Useful Library for Testing Django Projects

17.2 How to Structure Tests

“Flat is better than nested,”

popsicles/ |

17.3 How to Write Unit Tests

17.3.1 Each Test Method Tests One Thing

example:

# flavors/test_api.py |

17.3.2 For Views, When Possible Use the Request Factory

The django.test.client.RequestFactory provides a way to generate a request instance that can be used as the first argument to any view.

But the request factory doesn’t support middleware, including session and authentication.

from django.contrib.auth.models import AnonymousUser |

17.3.3 Don't Repeat Yourself Doesn't Apply to Writing Tests

17.3.4 Don't Rely on Fixtures

Rather than wrestle with xtures, we’ve found it’s easier to write code that relies on the ORM. Other people like to use third-party packages.(factory boy, model mommy, mock)

17.3.5 Things That Should Be Tested

Everything! Seriously, you should test whatever you can, including:

Views: Viewing of data, changing of data, and custom class-based view methods.

Models: Creating/updating/deleting of models, model methods, model manager methods.

Forms: Form methods, clean() methods, and custom elds.

Validators: Really dig in and write multiple test methods against each custom validator you write. Pretend you are a malignant intruder attempting to damage the data in the site.

Signals: Since they act at a distance, signals can cause grief especially if you lack tests on them.

Filters: Since lters are essentially just functions accepting one or two arguments, writing tests for them should be easy.

Template Tags: Since template tags can do anything and can even accept template context, writing tests often becomes much more challenging. This means you really need to test them, since otherwise you may run into edge cases.

Miscellany: Context processors, middleware, email, and anything else not covered in this list.

Failure What happens when any of the above fail?

17.3.6 Test for Failure

It is up to us to learn how to test for the exceptions our code my throw:

17.3.7 Use Mock to Keep Unit Tests From Touching the World

during tests we should not access external APIs, receive emails or webhooks, or anything that is not part of of the tested action.

when you are trying to write a unit test for a function that interacts with an external API, you have two choices:

- Choice #1: Change the unit test to be an Integration Test.

- Choice #2: Use the Mock library to fake the response from the external API.

Test list_flavors_sorted():

import mock import unittest |

Now let’s demonstrate how to test the behavior of the list flavors sorted() function when the Ice Cream API is innaccessible.

@mock.patch.object(icecreamapi, "get_flavors") |

As an added bonus for API authors, here’s how we test how code handles two different python- requests connection problems:

@mock.patch.object(requests, "get") |

17.3.8 Use Fancier Assertion Methods

- https://docs.python.org/2/library/unittest.html#assert-methods

- https://docs.python.org/3/library/unittest.html#assert-methods

- https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.8/topics/testing/tools/#assertions

We’ve found the following assert methods extremely useful:

- assertRaises

- Python 2.7: ListItemsEqual(), Python 3+ assertCountEqual()

- assertDictEqual()

- assertFormError()

- assertContains() Check status 200, checks in response.content.

- assertHTMLEqual() Amongst many things, ignores whitespace differences.

- assertJSONEqual()

17.3.9 Document the Purpose of Each Test

17.4 What About Integration Tests?

- Selenium tests to con rm that an application works in the browser.

- Actual testing against a third-party API instead of mocking responses. For example, Django Packages conducts periodic tests against GitHub, BitBucket, and PyPI API to ensure that its interaction with those systems is valid.

- Interacting with http://requestb.in or http://httpbin.org/ to confirm the validity of out-bound requests.

- Using http://runscope.com to validate that our API is working as expected.

17.5 Continuous Integration

For projects of any size, we recommend setting up a continuous integration (CI) server to run the project’s test suite whenever code is committed and pushed to the project repo.

17.6 Setting Up the Test Coverage Game

17.6.1 Step 1: Start Writing Tests

17.6.2 Step 2: Run Tests and Generate Coverage Report

In the command-line, at the <project root>, type:

$ coverage run manage.py test --settings=twoscoops.settings.test |

If we have nothing except for the default tests for two apps, we should get a response that looks like:

Creating test database for alias "default"... |

17.6.3 Step 3: Generate the Report!

In the command-line, at the <project root>:

$ coverage html --omit="admin.py" |

After this runs, in the <project root> directory there is a new directory called htmlcov/ . In the htmlcov/ directory, open the index.html file using any browser.

18 Documentation

18.1 Use reStructuredText for Python Docs

http://docutils.sourceforge.net/docs/ref/rst/restructuredtext.html

here is a quick primer of some very useful commands you should learn:

Section Header |

18.2 Use Sphinx to Generate Documentation From reStructuredText

Sphinx is a tool for generating nice-looking docs from your .rst les. Output formats include HTML, LaTeX, manual pages, and plain text.

Follow the instructions to generate Sphinx docs: http://sphinx-doc.org/.

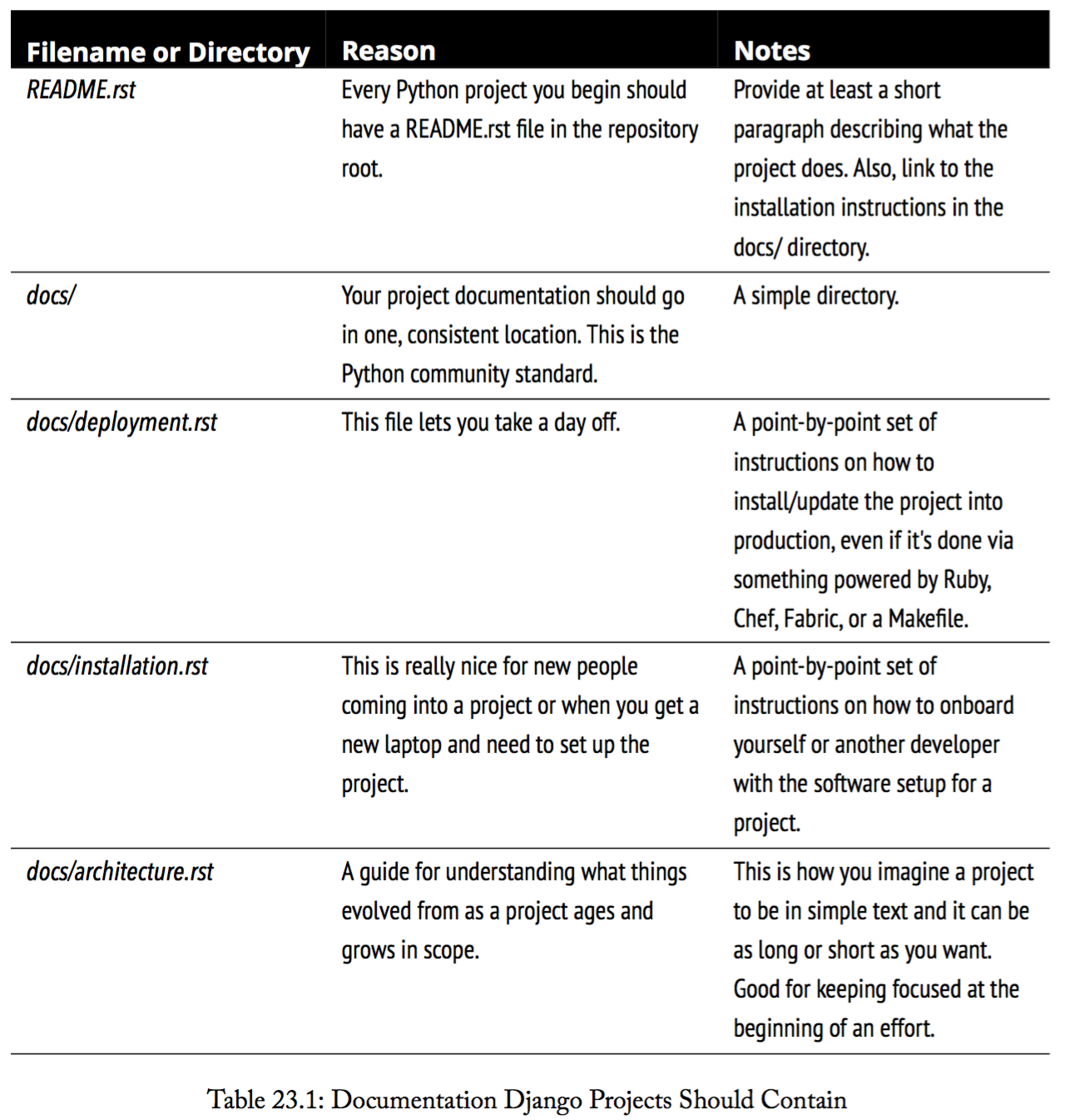

18.3 What Docs Should Django Projects Contain?

Here we provide a table that describes what we consider the absolute minimum documentation:

18.4 Additional Documentation Resources

- http://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0257 Official speci cation on docstrings.

- https://readthedocs.org/ Read the Docs is a free service that can host your Sphinx documentation.

- http://pythonhosted.org/ Python Hosted is another free service for documentation hosting.

19 Finding and Reducing Bottlenecks

19.1 Should You Even Care?

Remember, premature optimization is bad. If your site is small- or medium-sized and the pages are loading ne, then it’s okay to skip this chapter.

19.2 Speed Up Query-Heavy Pages

19.2.1 Find Excessive Queries With Django Debug Toolbar

You’ll find bottlenecks such as:

- Duplicate queries in a page.

- ORM calls that resolve to many more queries than you expected.

- Slow queries.

19.2.2 Reduce the Number of Queries

- Try using select_related() in your ORM calls to combine queries. It follows ForeignKey relations and combines more data into a larger query. If using CBVs, django-braces makes doing this trivial with the SelectRelatedMixin.

- For many-to-many and many-to-one relationships that can’t be optimized with select_related(), explore using prefetch_related() instead.

- If the same query is being generated more than once per template, move the query into the Python view, add it to the context as a variable, and point the template ORM calls at this new context variable.

- Implement caching using a key/value store such as Memcached. en write tests to assert the number of queries run in a view. See http://2scoops.co/1.8-test-num-queries for instructions.

- Use the django.utils.functional.cached_property decorator to cache in memory the result of method call for the life of an object instance. This is incredibly useful.

19.2.3 Speed Up Common Queries

- Make sure your indexes are helping speed up your most common slow queries. Look at the raw SQL generated by those queries, and index on the fields that you filter/sort on most frequently. Look at the generated WHERE and ORDER BY clauses.

- Understand what your indexes are actually doing in production. Development machines will never perfectly replicate what happens in production, so learn how to analyze and understand what’s really happening with your database.

- Look at the query plans generated by common queries.

- Turn on your database’s slow query logging feature and see if any slow queries occur frequently.

- Use django-debug-toolbar in development to identify potentially-slow queries defensively, before they hit production.

19.2.4 Switch ATOMIC REQUESTS to False

19.3 Know What Doesn't Belong in the Database

Three things that should never go into any large site’s relational database:

Logs. Don’t add logs to the database. Logs may seem OK on the surface, especially in development. Yet adding this many writes to a production database will slow their performance. When the ability to easily perform complex queries against your logs is necessary, we recommend third-party services such as Splunk or Loggly, or use of document-based NoSQL databases.

Ephemeral data. Don’t store ephemeral data in the database. What this means is data that re- quires constant rewrites is not ideal for use in relational databases. is includes examples such as django.contrib.sessions, django.contrib.messages, and metrics. Instead, move this data to things like Memcached, Redis, Riak, and other non-relational stores.

Binary Data

19.4 Cache Queries With Memcached or Redis

19.5 Identify Specific Places to Cache

Here are things to think about:

- Which views/templates contain the most queries?

- Which URLs are being requested the most?

- When should a cache for a page be invalidated?

19.6 Compression and Minification of HTML, CSS, and JavaScript

- Apache and Nginx compression modules

- django-pipeline

19.7 Use Upstream Caching or a Content Delivery Network

Upstream caches such as Varnish are very useful. They run in front of your web server and speed up web page or content serving signi cantly. See http://varnish-cache.org/.

Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) like Fastly, Akamai, and Amazon Cloudfront serve static me- dia such as images, video, CSS, and JavaScript les. ey usually have servers all over the world, which serve out your static content from the nearest location. Using a CDN rather than serving static content from your application servers can speed up your projects.

20 Asynchronous Task Queues

An asynchronous task queue is one where tasks are executed at a different time from when they are created, and possibly not in the same order they were created.

20.1 Do We Need a Task Queue?

Here is a useful rule of thumb for determining if a task queue should be used:

Results take time to process: Task queue should probably be used.

Users can and should see results immediately: Task queue should not be used.

| Use Task Queue? | Issue |

|---|---|

| Yes | Sending bulk email |

| Yes | Modifying files (including images) |

| Yes | Fetching large amounts of data from third-party Ice Cream APIs |

| Yes | Inserting or updating a lot of records into a table |

| No | Updating a user profile |

| No | Adding a blog or CMS entry |

| Yes | Performing time-intensive calculations |

| Yes | Sending or receiving of webhooks |

- Sites with small-to-medium amounts of traffic may never need a task queue for any of these actions.

- Sites with larger amounts of traffic may discover that nearly every user action requires use of a task queue.

20.2 Choosing Task Queue Software

Celery, Redis Queue, django-background-tasks, which to choose? Let’s go over their pros and cons:

| Software | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Celery | Defacto Django standard, many different storage types, flexible, full-featured, great for high volume | Challenging setup, overkill for slower traffic sites |

| Redis Queue | Flexible, powered by Redis, lower memory footprint then Celery, great for high volume, can use django-rq or not | Not as many features as Celery, medium difficulty setup, Redis only option for storage |

| django-background-tasks | Very easy setup, easy to use, good for small volume or batch jobs, uses Django ORM for backend | Uses Django ORM for backend, absolutely terrible for medium-to-high volume |

Here is our general rule of thumb:

- For most high-to-low volume projects, we recommend Redis Queue.

- For high-volume projects with the need for complex task management, we recommend Celery.

- For small volume projects, especially for running of periodic batch jobs, we recommend django-background-tasks

20.3 Best Practices for Task Queues

20.3.1 Treat Tasks Like Views

we recommend that views contain as little code as possible, calling methods and functions from other places in the code base. We believe the same thing applies to tasks.

you can put your task code into a function, put that function into a helper module, and then call that function from a task function.

20.3.2 Tasks Aren't Free

20.3.3 Only Pass JSON-Serializable Values to Task Functions

That limits us to integers, oats, strings, lists, tuples, and dictionaries. Don’t pass in complex objects.

Passing in an object representing persistent data (ORM instances for example can cause a race condition.)

20.3.4 Learn How to Monitor Tasks and Workers

Some useful tools:

- Celery: https://pypi.python.org/pypi/flower

- Redis Queue: https://pypi.python.org/pypi/django-redisboard for using Redis Queue directly.

- django-rq: https://pypi.python.org/pypi/django-rq for using django-rq.

- django.contrib.admin for django-background-tasks.

20.3.5 Logging!

20.3.6 Monitor the Backlog

As traffic increases, tasks can pile up if there aren’t enough workers. When we see this happening, it’s time to increase the number of workers.

20.3.7 Periodically Clear Out Dead Tasks

20.3.8 Use the Queue's Error Handling

- Max retries for a task

- Retry delays

When a task fails, we like to wait at least 10 seconds before trying again. Even better, if the task queue software allows it, increase the delay each time an attempt is made.

21 Security

21.1 Know Django's Security Features

Django 1.8’s security features include:

- Cross-site scripting (XSS) protection.

- Cross-site request forgery (CSRF) protection.

- SQL injection protection.

- Clickjacking protection.

- Support for TLS/HTTPS/HSTS, including secure cookies.

- Secure password storage, using the PBKDF2 algorithm with a SHA256 hash by default.

- Automatic HTML escaping.

- An expat parser hardened against XML bomb attacks.

- Hardened JSON, YAML, and XML serialization/deserialization tools.

21.2 Turn Off DEBUG Mode in Production

Keep in mind that when you turn off DEBUG mode, you will need to set ALLOWED HOSTS or risk raising a SuspiciousOperation error, which generates a 500 error that can be hard to debug.

21.3 Keep Your Secret Keys Secret

21.4 HTTPS Everywhere

21.4.1 Use django.middleware.security.SecurityMiddleware

The tool of choice for projects on Django 1.8+ for enforcing HTTPS/SSL across an entire site through middleware is built right in. To activate this middleware just follow these steps:

- Add django.middleware.security.SecurityMiddleware to the settings.MIDDLEWARE CLASSES definition.

- Set settings.SECURE SSL HOST to True.

django.middleware.security.SecurityMiddleware Does Not Include static/media, static assets are typically served directly by the web

server (nginx, Apache)

21.4.2 Use Secure Cookies

Your site should inform the target browser to never send cookies unless via HTTPS. You’ll need to set the following in your settings:

SESSION_COOKIE_SECURE = True |

21.4.3 Use HTTP Strict Transport Security (HSTS)

HSTS can be con gured at the web server level. Follow the instructions for your web server, platform- as-a-service, and Django itself (via settings.SECURE HSTS SECONDS).

21.4.4 HTTPS Configuration Tools

Mozilla provides a SSL con guration generator at the https://mozilla.github.io/server-side-tls/ssl-config-generator/

Once you have a server set up (preferably a test server), use the Qualys SSL Labs server test at https://www.ssllabs.com/ssltest/ to see how well you did.

21.5 Use Allowed Hosts Validation

We recommend that you avoid setting wildcard values here.

https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.8/ref/settings/#allowed-hosts

https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.8/ref/request-response/#django.http.HttpRequest.get_host

21.6 Always Use CSRF Protection With HTTP Forms That Modify Data

21.7 Obfuscate Primary Keys with UUIDs

import uuid as uuid_lib |

22 Logging

22.1 When to Use Each Log Level

In your production environment, we recommend using every log level except for DEBUG.

22.1.1 Log Catastrophes With CRITICAL

For example, if your code relies on an internal web service being available, and if that web service is part of your site’s core functionality, then you might log at the CRITICAL level anytime that the web service is inaccessible.

22.1.2 Log Production Errors With ERROR

whenever code raises an exception that is not caught, the event gets logged by Django using the following code:

# Taken directly from core Django code. |

we recommend that you use the ERROR log level whenever you need to log an error that is worthy of being emailed to you or your site admins.

22.1.3 Log Lower-Priority Problems With WARNING

This level is good for logging events that are unusual and potentially bad, but not as bad as ERROR- level events.

For example, when an incoming POST request is missing its csrf token, the event gets logged as follows:

# Taken directly from core Django code. |

22.1.4 Log Useful State Information With INFO

We recommend using this level to log any details that may be particularly important when analysis is needed. These include:

- Startup and shutdown of important components not logged elsewhere

- State changes that occur in response to important events

- Changes to permissions, e.g. when users are granted admin access

In addition to this, the INFO level is great for logging any general information that may help in performance analysis.

22.1.5 Log Debug-Related Messages to DEBUG

In development, we recommend using DEBUG and occasionally INFO level logging wherever you’d consider throwing a print statement into your code for debugging purposes.

import logging |

22.2 Log Tracebacks When Catching Exceptions

- Logger.exception() automatically includes the traceback and logs at ERROR level.

- For other log levels, use the optional exc_info keyword argument.

import logging import requests |

22.3 One Logger Per Module That Uses Logging

# You can place this snippet at the top |

If you’re running into a strange issue in production that you can’t replicate locally, you can temporarily turn on DEBUG logging for just the module related to the issue

22.4 Log Locally to Rotating Files

A common way to set up log rotation is to use the UNIX logrotate utility with log- ging.handlers.WatchedFileHandler.

Note that if you are using a platform-as-a-service, you might not be able to set up rotating log files. In this case, you may need to use an external logging service such as Loggly: http://loggly.com/.

22.5 Log settings files

23 Signals: Use Cases and Avoidance Techniques

Signals can be useful, but they should be used as a last resort, only when there’s no good way to avoid using them.

23.1 When to Use and Avoid Signals

Do not use signals when:

- The signal relates to one particular model and can be moved into one of that model’s methods, possibly called by save().

- The signal can be replaced with a custom model manager method.

- The signal relates to a particular view and can be moved into that view.

It might be okay to use signals when:

- Your signal receiver needs to make changes to more than one model.

- You want to dispatch the same signal from multiple apps and have them handled the same way by a common receiver.

- You want to invalidate a cache after a model save.

- You have an unusual scenario that needs a callback, and there’s no other way to handle it besides using a signal. For example, you want to trigger something based on the save() or init() of a third-party app’s model. You can’t modify the third-party code and extending it might be impossible, so a signal provides a trigger for a callback.

23.2 Signal Avoidance Techniques

23.2.1 Using Custom Model Manager Methods Instead of Signals

Let’s imagine that our site handles user-submitted ice cream-themed events, and each ice cream event goes through an approval process. These events are set with a status of “Unreviewed” upon creation. The problem is that we want our site administrators to get an email for each event submission so they know to review and post things quickly.

We could have done this with a signal, but unless we put in extra logic in the post save() code, even administrator created events would generate emails.

Use custom model manager instead of signals to solve above.

EventManager:

# events/managers.py |

Let’s attach it to our model (which comes with a notify admins() method:

# events/models.py |

To generate an event, instead of calling create(), we call a create event() method.

>>> from django.contrib.auth import get_user_model |

23.2.2 Validate Your Model Elsewhere

If you’re using a pre save signal to trigger input cleanup for a speci c model, try writing a custom validator for your eld(s) instead.

If validating through a ModelForm, try overriding your model’s clean() method instead.

23.2.3 Override Your Model's Save or Delete Method Instead

If you’re using pre save and post save signals to trigger logic that only applies to one particular model, you might not need those signals. You can often simply move the signal logic into your model’s save() method.

23.2.4 Use a Helper Function Instead of Signals

We find this approach useful under two conditions:

- Refactoring: Once we realize that certain bits of code no longer need to be obfuscated as signals and want to refactor, the question of ‘Where do we put the code that was in a signal?’ arises. If it doesn’t belong in a model manager, custom validator, or overloaded model method, where does it belong?

- Architecture: Sometimes developers use signals because we feel the model has become too heavyweight and we need a place for code. While Fat Models are a nice approach, we admit it’s not much fun to have to parse through a 500 or 2000 line chunk of code.

24 Utilities

24.1 Create a Core App for Your Utilities

TIP: Always make the core app a real Django app

Our core app would therefore look like:

core/ |

24.2 Optimize Apps with Utility Modules

Synonymous with helpers, these are commonly called utils.py and sometimes helpers.py.

24.2.1 Trimming Models

One day we notice that our fat model has reached brobdingnagian proprtions and is over a thousand lines of code.

We start looking for methods (or properties or classmethods) whose logic can be easily encapsulated in functions stored in flavors/utils.py.

24.3 Django's Own Swiss Army Knife

Most of the modules in django.utils are designed for internal use and only the following parts can be considered stable and thus backwards compatible

https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.8/ref/utils/

Some useful utils from django:

- django.contrib.humanize

- django.utils.decorators.method decorator(decorator)

- django.utils.decorators.decorator from middleware( middleware)

- django.utils.encoding.force text(value)

- django.utils.functional.cached property

- django.utils.html.format html(format str, args, **kwargs)

- django.utils.html.strip tags(value)

- django.utils.six

- django.utils.text.slugify(value)

- django.utils.timezone

- django.utils.translation

24.4 Exceptions

24.4.1 django.core.exceptions.ImproperlyConfigured

The purpose of this module is to inform anyone attempting to run Django that there is a con guration issue.

24.4.2 django.core.exceptions.ObjectDoesNotExist

We’ve found this is a really nice tool for working with utility functions that fetch generic model instances and do something with them. Here is a simple example:

# core/utils.py |

We can create our own variant of django's django.shortcuts.getobjector404 function, perhaps raising a HTTP 403 exception instead of a 404:

# core/utils.py |

24.4.3 django.core.exceptions.PermissionDenied

if something bad happens, instead of just returning a 500 exception, which may rightly alarm users, we simply provide a “Permission Denied” screen.

# stores/calc.py |

# urls.py |

24.5 Serializers and Deserializers

Django has some great tools for working with serialization and deserialization of data of JSON, Python, YAML and XML data.

Here is how we serialize data:

# serializer_example.py |

Here is how we deserialize data:

# deserializer_example.py |

using Django’s built-in serializers and deserializers: they can cause problems. From painful experience, we know that they don’t handle complex data structures well.

Consider these guidelines that we follow in our projects:

- Serialize data at the simplest level.

- Any database schema change may invalidate the serialized data.

- Don’t just import serialized data. Consider using Django’s form libraries to validate incoming data before saving to the database.

24.5.1 django.core.serializers.json.DjangoJSONEncoder

Python’s built-in JSON module can’t handle encoding of date/time or decimal types.

Fortunately for all of us, Django provides a very useful JSONEncoder class. See the code example below:

# json_encoding_example.py |

25 Deployment:Platforms as a Service

The most commonly-used Django-friendly PaaS companies as of this writing are:

- Heroku (http://heroku.com) is a popular option in the Python community well known for its documentation and add-ons system. If you choose this option, please read http://www.theherokuhackersguide.com/ by Randall Degges.

- PythonAnywhere (https://www.pythonanywhere.com) is a Python-powered PaaS that is incredibly beginner-friendly.

25.1 Automate All the Things!

Use simple automation using one of the following tools:

- Makefiles are useful for simple projects. Their limited capability means we won’t be tempted to make things too fancy. As soon as you need more power, it’s time to use something else. Something like Invoke as described in the next bullet.

- Invoke is the direct descendant of the venerable Fabric library. It is similar to Fabric, but is designed for running tasks locally rather than on a remote server. Tasks are de ned in Python code, which allows for a bit more complexity in task de nitions (although it’s easy to take things too far). It has full support for Python 3.4.

26 Deploying Django Projects

26.1 Single-Server for Small Projects

26.1.1 Example: Quick Ubuntu + Gunicorn Setup

- An old computer or cheap cloud server

- Ubuntu Server OS

- PostgreSQL

- Virtualenv

- Gunicorn

You can either use a computer that you have lying around your house, or you can use a cheap cloud server from a provider like DigitalOcean, Rackspace, or AWS.

installing at least these:

For pip/virtualenv python-pip, python-virtualenv

For PostgreSQL postgresql, postgresql-contrib, libpq-dev, python-dev

Then we do all the server setup basics like updating packages and creating a user account for the project.

At this point, it’s Django time. We clone the Django project repo into our user’s home directory and create a virtualenv with the project’s Python package dependencies, including Gunicorn. We create a PostgreSQL database for the Django project and run python manage.py migrate.

Then we run the Django project in Gunicorn. As of this writing, this requires a simple 1-line com- mand. See: https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.8/howto/deployment/wsgi/gunicorn/

adding nginx, Redis, and/or memcached, or setting up Gunicorn behind an nginx proxy.

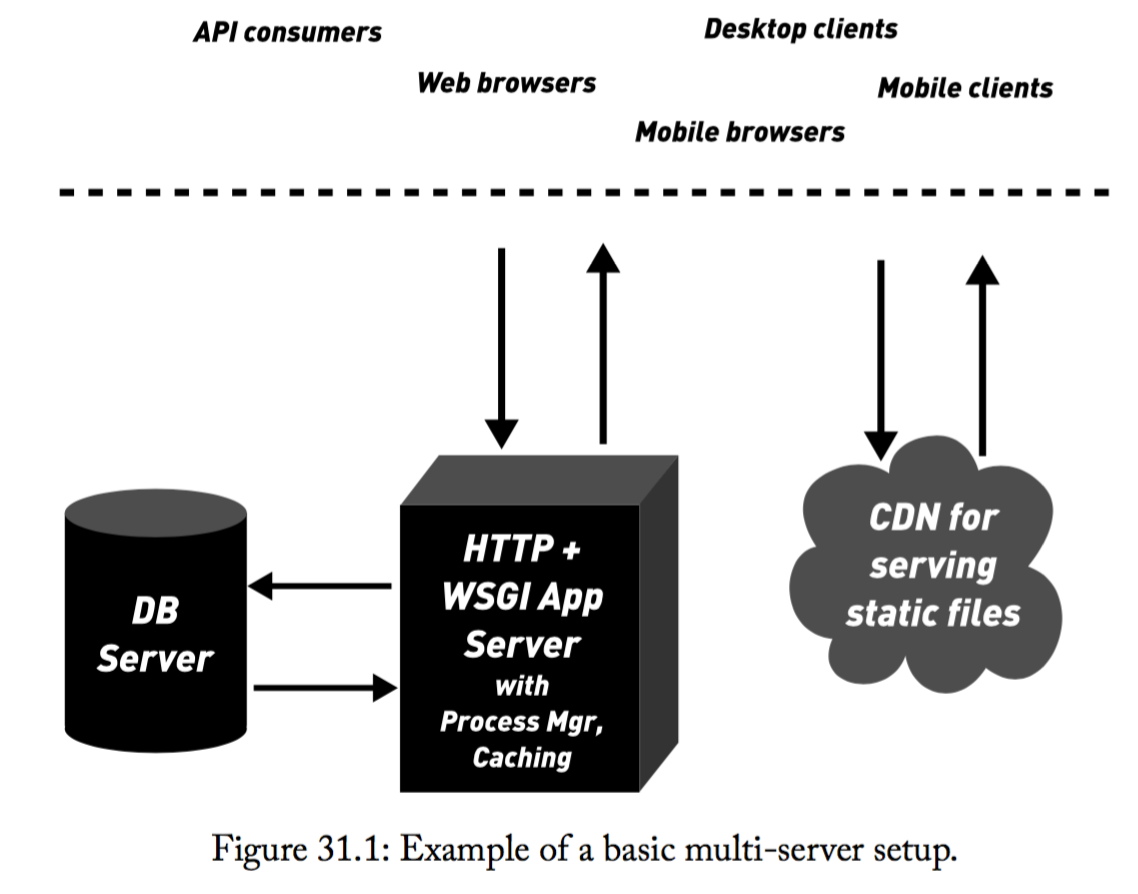

26.2 Multi-Server for Medium to Large Projects

This is what you need at the most basic level:

- Database server. Typically PostgreSQL in our projects when we have the choice, though Eventbrite uses MySQL.

- WSGI application server. Typically uWSGI or Gunicorn with Nginx, or Apache with mod wsgi.

Additionally, we may also want one or more of the following:

- Static file server. If we want to do it ourselves, Nginx or Apache are fast at serving static files. However, CDNs such as Amazon CloudFront are relatively inexpensive at the basic level.

- Caching and/or asynchronous message queue server. is server might run Redis, Memcached or Varnish.

- Miscellaneous server. If our site performs any CPU-intensive tasks, or if tasks involve waiting for an external service (e.g. the Twitter API) it can be convenient to offload them onto a server separate from your WSGI app server.

Finally, we also need to be able to manage processes on each server. We recommend in descending order of preference:

- Supervisord

- init scripts

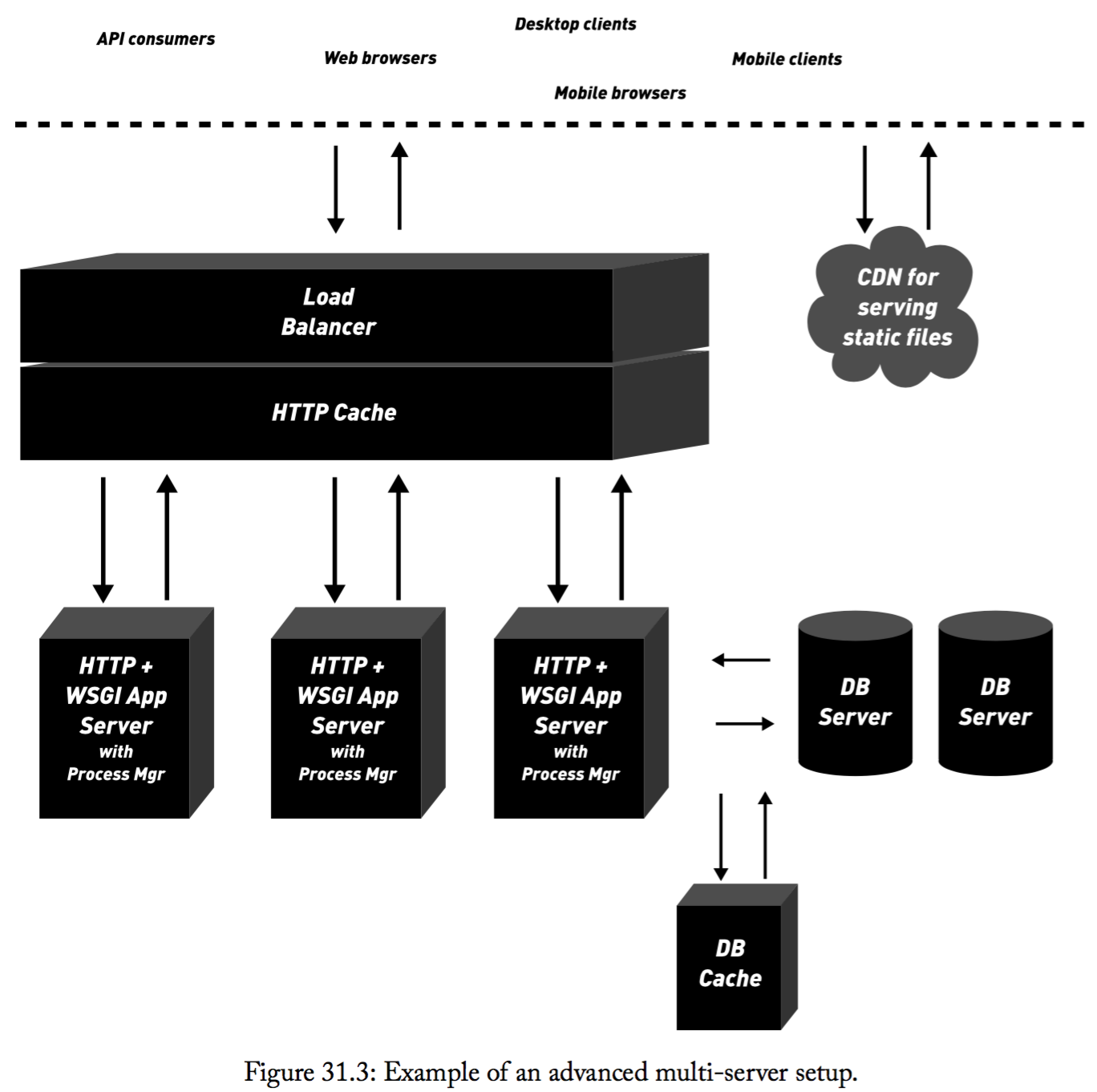

26.2.1 Advanced Multi-Server Setup

Load balancers can be hardware- or software-based. Commonly-used examples include:

- Software-based: HAProxy, Varnish, Nginx

- Hardware-based: Foundry, Juniper, DNS load balancer

- Cloud-based: Amazon Elastic Load Balancer, Rackspace Cloud Load Balancer

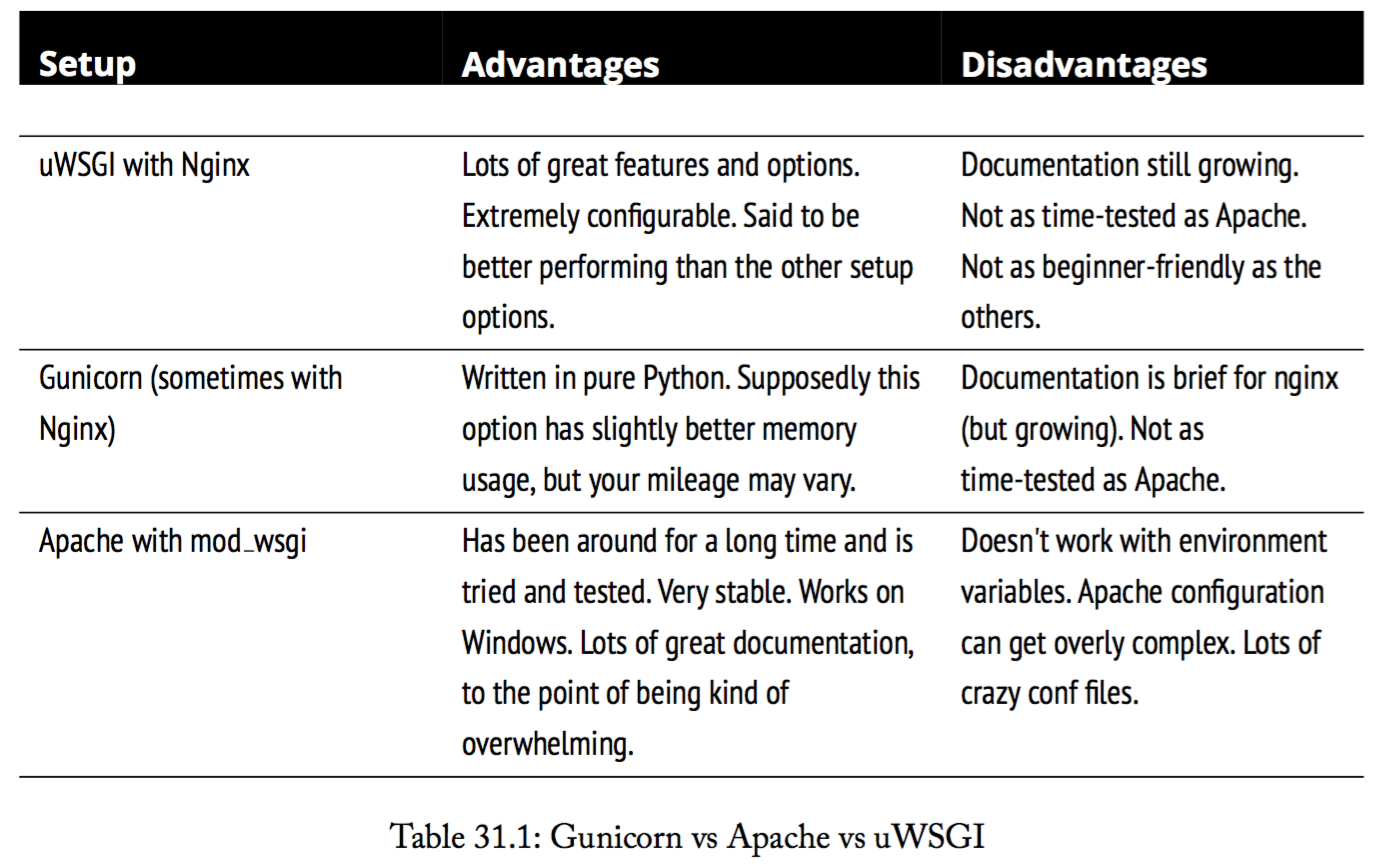

26.3 WSGI Application Servers

The most commonly-used WSGI deployment setups are:

- uWSGI with Nginx.

- Gunicorn behind a Nginx proxy.

- Apache with mod wsgi.

26.4 Automated, Repeatable Deployments

27 Continuous Integration

Here’s a typical development work ow when using continuous integration:

- Developer writes code, runs local tests against it, then pushes the code to an instance of a code repository such as Git or Mercurial. This should happen at least once per day.

- The code repository informs an automation tool that code has not been submitted for integration.

- Automation integrates the code into the project, building out the project. Any failures during the build process and the commit is rejected.

- Automation runs developer-authored tests against the new build. Any failures of the tests and the commit is rejected.

- The developer is notified of success or the details of failure. Based on the report, the developer can mitigate the failures. If there are no failures, the developer celebrates and moves to the next task.

27.1 Principles of Continuous Integration

27.1.1 Write Lots of Tests!

27.1.2 Keeping the Build Fast

- Avoid fixtures. This is yet another reason why we advise against their use.

- Avoid TransactionTestCase except when absolutely necessary.

- Avoid heavyweight setUp() methods.

- Write small, focused tests that run at lightning speed, plus a few larger integration-style tests.

- Learn how to optimize your database for testing. is is discussed in public forums like Stack Overflow: http://stackoverflow.com/a/9407940/93270

27.2 Tools for Continuously Integrating Your Project

27.2.1 Tox

http://tox.readthedocs.org/

This is a generic virtualenv management and testing command-line tool that allows us to test our projects against multiple Python and Django versions with a single command at the shell.

27.2.2 Jenkins

http://jenkins-ci.org/

Jenkins is a extensible continuous integration engine used in private and open source efforts around the world. It is the standard for automating the components of Continuous Integration, with a huge community and ecosystem around the tool.

27.3 Continuous Integration as a Service

There are various services that provide automation tools powered by Jenkins or analogues. Some of these plug right into popular repo hosting sites like GitHub and BitBucket, and most provide free repos for open source projects. Some of our favorites include:

| Service | Python Versions Supported | Link |

|---|---|---|

| Travis-CI | 3.3, 3.2, 2.7, 2.6, PyPy | https://travis-ci.org |

| AppVeyor (Windows) | 3.4, 3.3, 2.7 | http://www.appveyor.com/ |

| CircleCI | 3.4, 3.3, 2.7, 2.6, PyPy, many more | https://circleci.com |

| Drone.io | 2.7, 3.3 | https://drone.io/ |

| Codeship | 3.4, 2.7 | https://codeship.com |

27.3.1 Code Coverage as a Service

https://codecov.io can generate coverage reports

28 Debugging

28.1 Debugging in Development

28.1.1 Use django-debug-toolbar

If you don’t have it set up and con gured, stop everything else you are doing and add it to your project.

28.1.2 That Annoying CBV Error

twoscoopspress$ python discounts/manage.py runserver 8001 |

This error is caused because lack as_view() at urls.py

Example of TypeError generating code:

# Forgetting the 'as_view()' method |

Example of fixed code:

url(r'ˆ$', HomePageView.as_view(), name="home"), |

28.1.3 Master the Python Debugger

ipdb(ipdb does is add the ipython interface to the PDB interface) is also very useful

References:

- Python’s pdb documentation: https://docs.python.org/2/library/pdb.html

- IPDB: https://pypi.python.org/pypi/ipdb

- Using PDB with Django: https://mike.tig.as/blog/2010/09/14/pdb/

28.1.4 Remember the Essentials for Form File Uploads

There are two easily forgotten items that will cause file uploads to fail silently.

check the following:

- Does the <form> tag include an encoding type?

<form action="{% url 'stores:file_upload' store.pk %}" |

- Do the views handle request.FILES? In Function-Based Views?

# stores/views.py |

Or what about Class-Based Views?

# stores/views.py |

If a view inherits from one of the following then we don’t need to worry about re- quest.FILES in your view code. Django handles most of the work involved.

- django.views.generic.edit.FormMixin

- django.views.generic.edit.FormView

- django.views.generic.edit.CreateView

- django.views.generic.edit.UpdateView

28.2 Debugging Production Systems

28.2.1 Read the Logs the Easy Way

use a log aggregator like Sentry get a better view into what is going on in your application.

28.2.2 Mirroring Production

28.2.3 UserBasedExceptionMiddleware

What if you could provide superusers with access to the settings.DEBUG=True 500 error page in production?

there is a way to use this powerful debugging tool in production.

# core/middleware.py |

28.2.4 That Troublesome settings.ALLOWED HOSTS Error

Unfortunately, as soon as settings.DEBUG is False, a project with an incorrectly set ALLOWED_HOSTS will generate constant 500 errors. Checking the logs will show that SuspiciousOperation errors are being raised, but those errors don’t come with a meaningful message.

Therefore, whenever a project is deployed for the first time and always returns a 500 error, check settings.ALLOWED HOSTS. As for knowing what to set, here is a starting example:

# settings.py |

28.3 Feature Flags

Feature Flags allow us to turn a project’s feature on or off via a web-based interface.

What if we could allow a subset of real users (i.e. ‘beta users’) defined through an admin-style interface to interact with a new feature before turning it on for everyone?

This is what feature ags are all about!

28.3.1 Feature Flag Packages

28.3.2 Unit Testing Code Affected by Feature Flags

One gotcha with feature ags is running tests against code that are turned off by them. How do we know that our new feature is tested when the flag to run them is turned off?

The answer to this question is that our tests should cover both code paths, with feature flags on or off. To do this, we need to familiarize ourselves with how to turn a feature ag on or off within the Django testing framework:

29 Internationalization and Localization

29.1 Define Python Source Code Encodings

at the top each module add:

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*- |

29.2 Wrap Content Strings with Translation Functions

https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.8/topics/i18n/translation/

| Function | Purpose | Link |

|---|---|---|

| ugettext() | For content executed at runtime, e.g. form validation errors. | https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.8/topics/i18n/translation/#standard-translation |

| ugettext lazy() | For content executed at compile time, e.g. verbose name in models. | https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.8/topics/i18n/translation/#lazy-translation |

| string concat() | Replaces the standard str.join() method for joining strings. Rarely used. | https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.8/topics/i18n/translation/#localized-names-of-languages |

29.2.1 Convention: Use the Underscore Alias to Save Typing

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*- |

29.3 Don't Interpolate Words in Sentences

Bad Example:

# DON'T DO THIS! |

want to change above to international string but it does not works:

# DON'T DO THIS! |

improve above:

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*- |

29.4 Unicode Tricks

- Python 3 Can Make Unicode Easier

- Use django.utils.encoding.force text() Instead of unicode() or str()

29.5 Browser Page Layout

Assuming you’ve got your content and Django templates internationalized and localized, you can discover that your layouts are broken.

Mozilla’s answer is to determine the width of a title container, then use JavaScript adjust the font size of the title text downwards until the text fits into the container with wrapping.

30 Security Settings Reference

| Setting | Development | Production |

|---|---|---|

| ALLOWED_HOSTS | any list | see previous chapter |

| DEBUG | True | False |

| DEBUG_PROPAGATE_EXCEPTIONS | False | False |

| Email SSL | see below | see below |

| MIDDLEWARE_CLASSES | Standard | AddSecurityMiddleware |

| SECRET_KEY | Use cryptographic key | see previous chapter |

| SECURE_PROXY_SSL_HEADER | None | see below |

| SECURE_SSL_HOST | False | True |

| SESSION_COOKIE_SECURE | False | True |

| SESSION SERIALIZER | see below | see below |

30.1 Email SSL

https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.8/ref/settings/#email-use-tls

- EMAIL_USE_TLS

- EMAIL_USE_SSL

- EMAIL_SSL_CERTFILE

- EMAIL_SSL_KEYFILE

30.2 SESSION SERIALIZER

SESSION SERIALIZER = django.contrib.sessions.serializers.JSONSerializer.

30.3 SECURE PROXY SSL HEADER

For some setups, most notably Heroku, this should be:

SECURE PROXY SSL HEADER = (`HTTP X FORWARDED PROTO', `https')

31 Some Useful Packages

31.1 Core

- django-debug-toolbar http://django-debug-toolbar.readthedocs.org/ Display panels used for debugging Django HTML views.

- ipdb https://pypi.python.org/pypi/ipdb IPython-enabled pdb

- Sphinx http://sphinx-doc.org/ Documentation tool for Python projects.

31.2 Asynchronous

- celery http://www.celeryproject.org/ Distributed task queue.

- django-rq https://pypi.python.org/pypi/django-rq A simple app that provides django integration for RQ (Redis Queue).

- django-background-tasks https://pypi.python.org/pypi/django-background-tasks Database backed asynchronous task queue.

31.3 Deployment

- Invoke https://pypi.python.org/pypi/invoke Like Fabric, also works in Python 3.

- Supervisor http://supervisord.org/ Supervisord is a client/server system that allows its users to monitor and control a number of processes on UNIX-like operating systems.

31.4 Forms

- django-crispy-forms http://django-crispy-forms.readthedocs.org/ Rendering controls for Django forms. Uses Twitter Bootstrap widgets by default, but skinnable.

- django- oppyforms http://django-floppyforms.readthedocs.org/ Form field, widget, and layout that can work with django-crispy-forms.

31.5 Logging

- Sentry http://getsentry.com Exceptional error aggregation, with an open source code base.

31.6 Project Templates

- cookiecutter-django https://github.com/pydanny/cookiecutter-django The sample project layout detailed in chapter 3 of this book.

- Cookiecutter http://cookiecutter.readthedocs.org Not explicitly for Django, a command-line utility for creating project and app templates. It’s focused, heavily tested and well documented. By one of the authors of this book.

31.7 REST APIs

- django-rest-framework http://django-rest-framework.org/ The defacto REST package for Django. Exposes model and non-model resources as a RESTful API.

31.8 Testing

- coverage http://coverage.readthedocs.org/ Checks how much of your code is covered with tests.

- mock https://pypi.python.org/pypi/mock Not explicitly for Django, this allows you to replace parts of your system with mock objects. This project made its way into the standard library as of Python 3.4.

- tox http://tox.readthedocs.org/ A generic virtualenv management and test command line tool that allows testing of projects against multiple Python version with a single command at the shell.

31.9 Views

- django-braces http://django-braces.readthedocs.org Drop-in mixins that really empower Django’s class-based views.

31.10 Feature Flag

32 Reference

此筆記大多來自這本書:

Two Scoops of Django: Best Practices for Django 1.8

by Daniel Roy Greenfeld (Author), Audrey Roy Greenfeld (Author)

https://www.twoscoopspress.com/

Render by hexo-renderer-org with Emacs 25.2.1 (Org mode 8.2.10)